Many ancient cultures revered red, including the indigenous cultures of the Andes Mountains. Red, the color of blood, has historically been associated with danger, courage, and sacrifice. From the earliest times, people dusted corpses in burials with red ochre from iron oxides, or vermillion from mercury-containing cinnabar. When dyeing textiles became important cultural traditions, people highly valued red colors. In South America, ancient Andean artists happened upon an extremely vivid red dye: cochineal, which has been called “a perfect red”. Thousands of years later, the use of cochineal continues today. This draws attention from people across our societies, from those who grow it for export, those who consider it cruel and want to ban the usage, and those who are working to synthesize an alternative.

I learned about this dye when I spent a week on a volunteer service project at Capitol Reef National Park in Utah. One sunny afternoon, a few of us had the good fortune of joining a Park Service archaeologist to tour the remains of ancient Native American residence sites. Midway through the tour, the archaeologist pulled a tiny insect off a prickly pear pad, placed it on her palm, and crushed it with her fingernail. A remarkably large quantity of a bright red liquid — cochineal — appeared. Impressive! Then, only a few weeks later, by chance I caught an exhibit about cochineal at the Museum of International Folk Art in Santa Fe, New Mexico. The exhibit had descriptions of the history of this unique dye, and displays of cochineal-containing textile items, ranging from ancient fragments to evening gowns specifically designed to highlight the exceptional red tones of this dye. It was a fascinating and fabulous display!

The scale insect Dactylopius coccus and Opunia sp. (Wikipedia)

Insects and Incas

A tiny scale insect (Dactylopius coccus), closely related to aphids, is the source of cochineal. This insect contains cochineal-containing carminic acid that is a deterrent to predators. The scale insects grow and feed on American cactus belonging to the genus Opuntia, or prickly pear. Cochineal most likely originated in the Oaxaca region of Mexico. The timing of when or how the insect was transported into the Andes Mountains is unknown. Genetic tests show the D. coccus species found in Mexico and in Peru are surviving because of human care–that is, we thoroughly domesticated these insects–and their wild ancestors are likely extinct. The females lack all traces of wings and males have a single pair of wings and no mouth parts. (Some insects are really weird…)

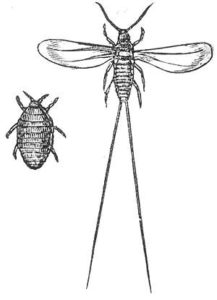

Female (left) and male (right) cochineals; by Henry Hartshorne, MD in “The Houshold Cyclopedia” printed in 1881. (Wikipedia)

To make cochineal dye, the bodies of the scale insects can be brushed or plucked from the cactus pads, boiled briefly, then dried and ground into a powder. The carminic acid dye is extracted using heat treatments that include boiling the dried powder in water along with additions of high pH (or basic) chemicals, such as ammonia or calcium carbonate. Controlling these chemical additions, along with water temperature and exposure to sunlight, produces an extremely wide range of colors that can vary from a deep crimson red to a bluish purple to a bright pink.

Cochineal became the primary source of red dye for Andean textiles beginning around the third century CE, although people may have used it much earlier. Artists from the major Andean cultures, from the Nazca and Moche through the Incas, used cochineal. They could produce various reddish shades depending on the white, gray, brown, or even black colors of the llama and alpaca wool yarn used, as well as the preferences of the different cultures. The Incas produced cochineal-dyed garments with a range of red, plus a purplish-blue color that required special knowledge and skill. They valued the red and blue combination as an important pairing, or duality (similar to gold-silver and male-female).

Slit tapestry shirt fragment, Chancay culture, central coast of Peru, circa 1000-1470 CE, alpaca wool dyed with saffron, cochineal, and indigo (Wikipedia)

Spanish conquistadores recognized the high value of cochineal when they first found cakes of this material in Aztec markets. In 1523, they reported these cakes to the King of Spain as a potentially important dye for European textile manufacturers. After cochineal began to be exported to Europe, it was received with great enthusiasm. Vivid, fire red scarlet was a color prized by painters and the wealthy members of the society. The dazzling hues and colorfast characteristics of cochineal far surpassed any other red dyes available. For decades, cochineal was the third most valuable export from the New World after gold and silver.

Duchess of Alba by Francisco de Goya, 1795; the bright red accents are probably cochineal (scraping off paint samples for chemical analysis is typically frowned on….) (Wikipedia)

Cochineal in Modern Times

The demand for cochineal was reduced dramatically when researchers developed synthetic red pigments in the mid-nineteenth century. In recent decades, however, natural dyes including cochineal have gained favor as part of a trend to reduce artificial ingredient usage. Cochineal provides appealing pink to red colors to many food products today, including juices, flavored yogurt, and candy, as well as to cosmetic products such as lipstick and shampoo.

Peru exports about 85% of the global supply of cochineal, with Mexico, the Canary Islands of Spain, Chile, Argentina, and other countries producing the rest. Traditional production and harvesting methods are labor intensive, and as demand rises, prices are increasing. Some scientists have been experimenting with genetic engineering to produce carminic acid more quickly and cheaply. This involves manipulating various enzymes in microbes that can produce the acid. Fine tuning the process, as well as scaling it up for industrial production, is still in the future.

Starbucks hit a public relations minefield in 2012 when an employee allegedly read the list of ingredients in their Strawberry Frappuccino drinks, recognized cochineal, and blew the whistle. Public outrage (the “Ewww!” factor), especially from vegans, ensued and Starbucks quickly pulled the pink drinks from the menu.

And, not surprisingly, there are insect-rights advocates who object to cochineal production. A post I found on the Effective Altruism Forum outlined the grim statistics, including that growers destroy about 22 billion to 89 billion adult female insects each year to meet the demand for carmine dye. Hmmm.

Insects play essential roles on our planet. However, I’ll admit that I’ve swatted lots of annoying mosquitos and flies over the years – and I despise ticks. So, I can’t get too worried about killing domesticated insects, even those that are cultivated only to produce attractive (if non-essential) dyes. When viewed from a global perspective, there are so many more compelling issues for concern that for me, scale insect slaughter seems small. Nonetheless, I appreciate that some people don’t want to harm any other living creatures, including insects.

Synthetic cochineal could solve the problem for consumers who prefer to avoid animal-based products. The microbes used and genetic modifications required, however, may be a cause for objection by some. One solution: avoid any pink or red manufactured products! We live in a complicated world; we are also fortunate to have choices.

If you liked this post, please share it and/or leave a comment below – thanks! And if you’d like to receive a message when I publish a new post, scroll down to the bottom of this page and leave your email address on my website. Join now to learn more about geology, geography, culture, and history.

SOURCES

Miller, Brittney J., 2022, “Scientists are making cochineal, a red dye from bugs, in the lab” in Smithsonian Magazine, March 29. Scientists Are Making Cochineal, a Red Dye From Bugs, in the Lab | Innovation| Smithsonian Magazine

Museum of International Folk Art (Santa Fe), Barbara C. Anderson, Blair Clark, and Carmella Padilla. A red like no other: how cochineal colored the world: an epic story of art, culture, science, and trade. Skira Rizzoli, New York, 2015.

Rowe, Abraham, 2020, Global cochineal production: scale, welfare concerns, and potential interventions in Effective Altruism Forum https://forum.effectivealtruism.org/posts/tDYtn4DhFsR7pR35i/global-cochineal-production-scale-welfare-concerns-and

Photo of the scale insect Dactylopius coccus and Opunia sp. by Dick Culbert from Gibsons, B.C. Canada https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Dactylopius_coccus_(8410000864).jpg

Drawing of female (left) and male (right) cochineals; by Henry Hartshorne, MD in “The Houshold Cyclopedia” printed in 1881. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carminic_acid#/media/File:Cochineal_drawing.jpg

Photo of slit tapestry shirt fragment, Peru, Chancay, central coast, c. 1000-1470 AD, alpaca wool dyed with saffron, cochineal, and indigo – Krannert Art Museum. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cochineal#/media/File:Slit_tapestry_shirt_fragment,_Peru,_Chancay,_central_coast,_c._1000-1470_AD,_alpaca_wool_dyed_with_saffron,_cochineal,_and_indigo_-_Krannert_Art_Museum,_UIUC_-_DSC06400.jpg

Painting of the Duchess of Alba by Francisco de Goya, 1795; the bright red accents are probably cochineal. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Goya_Alba1.jpg

Thanks, Roseanne.

What a fascinating story. And what a world we live in. Even extracting dye from insects generates controversy.

George

Thanks, George! Yes — there are many interesting aspects to the cochineal story!

Insects and humans… what can I say. I was on BART Wed and two people were freaking out over a poor moth that was flying around the car trying to find a way out. I caught it and let it go at West Oakland. They were grossed out. Del Monte dealt with this yuck factor in the 90s when we switched to carmine dye for cherries. We told those that were concerned that it was much safer than red dye #5.

Interesting, Steve — thanks! I figured an entomologist would have some good comments!

I’ve talked a lot about Cochineal on my guided hikes and river trips and can use much of this information in the future – thank you!

Great! Thanks, Wayne!

To tell the truth, it is so cool that you enlightened me about the history because before this moment I hadn’t been aware of many mentioned facts and it is so cool to open them to myself. Actually, red has a unique concept and can symbolize absolutely different things. This story of “a perfect red” vivid red dye blew my mind because before this moment I hadn’t been able to imagine something like this. It is direct confirmation of the fact that our world keeps an immense amount of unique and not fully studied things. Of course, Cochineal can perform such a significant function and this insect can give us a significant product, but I think that humanity is above all. I think that we need to make the care of living creatures a priority and not to exploit them for such selfish goals because, in my opinion, it will never lead to something good.

Thanks for your comment, Marina!