Iceland is a fabulous showcase for volcanoes. Fire and ice have combined to produce the backdrop of a stunning landscape, with red-hot eruptions providing the action on the stage. The location of Iceland–cut by a major rift zone and above a hotspot–is unique. And the easily accessible locations to view explosions of fiery lava and ash provide unusual opportunities for volcano-appreciators of all types, giving them ringside seats for the action. In the past few decades, there have been several spectacular volcanic performances.

The most recent eruption is a major mass-tourist attraction. The Geldingadalur eruption near Fagradalsfjall on the Reykjanes Peninsula is only about 25 miles (40 km) from the capital city, Reykjavík. Beginning on March 18, 2021, swarms of locals have been making the trek to admire this volcano; over the months since, many scientists and tourists from other nations have joined the audience. How the eruption has progressed–and what may happen in the future–are covered in detail, along with lots of photos and video links, in excellent blog posts by Albert on the Volcano Café website. The most recent post is here: https://www.volcanocafe.org/escape/ but others that Albert has published in past months also provide fascinating details.

People on the slopes of Fagradalsfjall, watching the Geldingadalir eruption on March 24, 2021

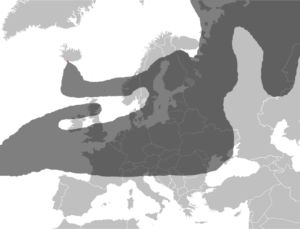

The 2010 Eyjafjallajökull eruption is renowned for spreading volcanic ash across northern and central Europe. The action began in April 2010 and continued for about 3 months. Although this eruption was of only moderately large size, it produced enormous quantities of highly abrasive glass particles when erupting lava cooled rapidly under a thick layer of glacial ice. Explosive bursts of power, fueled by the combination of meltwater and lava, injected the glass-rich ash plume directly into the jet stream. High-altitude winds quickly carried this ash southeast over the populated areas and into the heavily used airspace over Europe. Although they couldn’t see the erupting volcano, tens of thousands of people experienced disruptions to their lives.

Approximate drawing of estimated ash cloud from the Eyjafjallajökull eruption as of 17 April 2010 at 18:00 UTC

Formation of the volcanic island Surtsey offshore from November 1963 until June 1967 provided exceptional views to audiences worldwide through the miracle of glowing black and white television. This eruption began about 430 feet (130 m) below sea level offshore near the southern edge of Iceland and reached a maximum size of about 1.0 square mile (2.7 sq km). Boatloads of scientists, journalists, and photographers descended on this remote part of the planet and sent information about the eruption into the homes of millions. (At some point, a memorable movie about the birth of Surtsey was shown in one of my high school classrooms in California–quite a compelling story, which helped to pique my interest in geology!) Now, Surtsey is slowly breaking apart from wave erosion, and sometime in the next few centuries it will probably vanish beneath the ocean waves.

The island of Surtsey erupting in 1963 (NOAA)

The Icelandic Theater

Attempting to control nature can be quite challenging, although, of course, people have been trying for thousands of years. Volcanic eruptions are especially difficult to “manage”. Military-types use the term “theater” to define land or sea areas to be invaded or defended. And in battling volcanoes, the key aim is to defend human structures from being engulfed in flames or obliterated by burial in lava, so use of the term “theater” seems appropriate.

In the latest Geldingadalur eruption on the Reykjanes Peninsula, spreading lava has so far been largely restricted to a series of uninhabited valleys. Nonetheless, roads and buried telecommunication cables are threatened by invading lava, so defensive barrier walls were hastily constructed. Ranging in height up to about 16 feet (5 m) and in length to 656 feet (200 m), the results from this war on lava have been mixed. Sometimes, the lava has been slowed or stopped (at least temporarily) — but other flows have overtopped the new walls, with no regard for the hard work of humans. Eventually, the lava may find a course into the sea, creating new real estate in Iceland.

Top honors for efforts to control a volcano should be awarded to those who fought the famous Eldfell eruption on the island of Heimaey in southern Iceland. This 1973 eruption began unexpectedly in the middle of the night, and on the outskirts of Vestmannaeyjara, a fishing community of about 5,300 people living next to what many consider Iceland’s most important harbor. As the loud explosions and fire fountains of the eruption began, the town residents were nearly all hastily evacuated in fishing boats. Favorable winds, topography that initially channeled early lava flows away from the town, and an abundance of boats in the harbor allowed evacuation of the town within hours–preventing what could have been a major disaster. Those who remained on the island watched in dismay as, days later, the lava flowed through the town and headed for the harbor.

Eruption of Eldsfell behind Vestmannaeyjar in 1973

The harbor is the essential reason for the town, so a valiant fight to control the fiery lava flows began. Over the course of weeks, people assembled dozens of large pumps to blast millions of gallons of seawater on the hot lava, cooling and slowing the advancing front. To bring water farther into the flow, bulldozers moved across it and pipelines were placed; the cold water flowing through the pipes prevented them from melting. The battle continued for several weeks, while the eruption was gradually slowing, again, a strategic advantage for the people.

In late June 1973, the Eldfell eruption finally ceased. About one third of the houses in town were destroyed, and the harbor had narrowed but was still useable. People used the spoils of the war to their advantage–heat from the slowly cooling lava was harnessed to heat houses for about 15 years, and the abundant volcanic ash and rock were used to build a new and extended airport runway. A 656 feet (200 m) tall cone of Eldfell now rises above the town, a good vantage point to provide sweeping views of the island.

View of Vestmannaeyjar from the Eldsfell volcano in 2013; harbor entrance is on the right side of the photo

More details and excellent 1973 photos and videos of the town and this eruption are in a Volcano Café post by Albert, here: https://www.volcanocafe.org/the-heimaey-story/. The dramatic story of this battle, complete with descriptions of the colorful players involved, is also told in John McPhee’s excellent book published in 1989, The Control of Nature — highly recommended.

The Spectacular Scenery of Iceland

Why is Iceland such a superb theater for volcanic eruptions? There are around 30 active volcanic systems in Iceland, and about half of these have erupted since people settled in Iceland in 874 CE. The island is astride the Mid-Atlantic Ridge, the rift zone where two tectonic plates, the North American and Eurasian plates, are diverging. Rift zones are where magma rises upward from deep down in the Earth, filling the gaps that develop as tectonic plates move apart. Iceland also lies above a hotspot, where more hot magma is moving upwards from the Earth’s mantle, creating volcanoes like those beneath the Hawaiian Islands and the Yellowstone region of the United States.

The rugged mountains, sparkling waterfalls, rocky beaches–and of course volcanoes–give Iceland spectacular scenic beauty. I’ve had the good fortunate to visit Iceland twice, and although I’ve missed seeing a fiery eruption, I’ve seen a lot of other wonderful scenes (a few of my photos are in this post). As for other beautiful landscapes in Iceland, geologist Wayne Ranney has captured many spectacular ones on his website Earthly Musings in posts documenting his recent trip around this country. The link to his last trip post is here: Final Thoughts on Leaving Iceland — but scroll back in the website to see his earlier trip reports. Iceland is an amazing place!

Please share this post! Also, please scroll down to the bottom of this page and leave your email address on my website. You’ll receive messages only when I publish a new post (about once a week) and my occasional newsletter. Join now to learn more about geology, geography, culture, and history.

My friend is going to Iceland in may so I sent her your article Interesting and beautiful place Thanks for the information

Thanks, Robin!

I remember being impressed by McPhee’s account of “pissing on the lava”. Thanks for another great article.

Thanks, Larry! McPhee’s books about geologic topics have always been entertaining and informative!

Roseanne, The New Yorker magazine just ran a laudable piece on Iceland’s volcanoes. It is unbelievable to me how many people flock to places I consider too dangerous for my health.

I guess to each his own…..

Thanks, Karen! Yes – I saw that article – and also thought the journalist took some unwise chances. Just breathing bad air near a volcano can be deadly….

Great article and good links to other interesting volcanic activity. Reading this reminded me how long I’ve been wanting to go to Iceland. You inspired me and I’m will be going in June for 3 weeks.

Great to hear! Iceland is fabulous! Thanks for the comment, Jo Ann!