In the Andes Mountains of South America, the Incas and their ancestors invested enormous amounts of time and labor in the meticulous work of quarrying, transporting, and fitting together multi-ton stone blocks, or megaliths, for monumental construction projects. The temples and palaces that they built are iconic symbols of ancient Andean cultures. When I first visited archaeological sites Peru, I was captivated by the fine stonework and curious about where the massive stone blocks were quarried, and how they were moved and then fit into place.

The ancient Andean stonework is so impressive that many have found it difficult to believe that mere humans, who lacked draft animals and were using only stone-age tools, could be responsible for the construction. Some have alleged that the structures were built by a race of giants and others have attributed it to satanic assistance. Stone-softening acids from local plants have been proposed, either to cut the stone or to soften it so that it could be poured or compacted into molds. Lasers that focused sunlight with large parabolic gold mirrors have been suggested for stone cutting, as has extraterrestrial intervention. In local folklore, the Incas are even credited with knowing how to make the rocks walk by themselves. There is LOTS of misinformation out there.

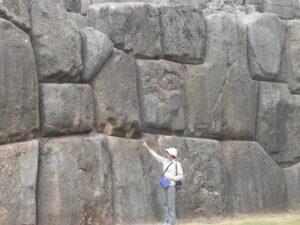

Terrace wall at Sacsayhuaman. I’m pointing at carved divets that might have been used with logs to prop up the block during fittings.

Carefully collected evidence, however, makes it clear that all construction tasks by the ancient Andeans were accomplished using human labor. Archaeologists have recovered ancient stone tools left in quarries and construction sites, they have studied the accounts of 16th century writers who watched the Incas building Spanish Colonial structures, and they have performed stone-cutting experiments in Inca quarries. Difficult as it is for some to believe, this research clearly indicates that simple tools and highly labor-intensive methods were the construction techniques employed by the Incas and their ancestors.

Natural Quarries

To begin, the ancient stoneworkers took advantage of “natural quarries”, in which the inherent tendencies of some rocks to break and form ready-made blocks were utilized. Mountain building processes throughout the Andes have been folding rocks over millions of years – and this can open cracks or joints in regular patterns across large sections of rock. In some areas of exposed bedrock, these joints break the rock into rough blocks in convenient sizes for construction, and these naturally occurring slabs can be collected and shaped relatively easily. Wedges could be pounded into cracks that had formed naturally, or that were accentuated or even started with stone tools, eventually splitting the rock apart. In some cases, water may have been used to help force rocks apart. By pounding wooden wedges into cracks, and holding the moisture in place with the wood, clay, or pitch, the night frosts at high altitudes would freeze the water and the expanding ice could eventually crack the rock.

There is a natural quarry at Machu Picchu, and this was probably a key factor in site selection. Construction of the terraces that support the buildings and other underground preparation work at the site required an estimated 60 percent of the construction effort. Having a nearby source for the tens of thousands of pounds of rock needed was a great asset.

Natural rock quarry (foreground) at Machu Picchu

Many of the most important buildings in the imperial Inca city of Cusco were constructed of the volcanic rock andesite, obtained primarily from the Rumiqolqa quarry, about 22 miles to the east. Inca blocks abandoned in varying stages of production can still be seen in this quarry, which continues to be worked today. The massive blocks used for construction at Sacsayhuaman were quarried from several places, including nearby for huge igneous diorite blocks, limestone from about 9 miles distant, and andesite that probably originated from the Rumiquoqa quarry. Evidence from many Andean archaeological sites indicates that thick ropes, and enormous amounts of human muscle power, were used to drag the stones from quarries to building sites.

Nibbling and Biting Bits of Rock

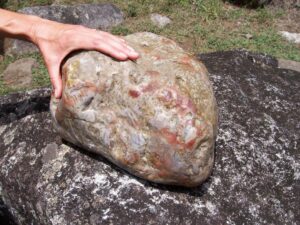

Rough stone blocks were shaped into final forms by chipping away at the rock bit by bit, in a process called “nibbling”. The primary tools used were hammerstones, composed of hard and rounded rocks typically collected from riverbeds. These were used in a set having decreasing sizes. Craftsmen would take large “bites” of rock with large hammerstones to begin shaping blocks and use progressively smaller ones as final trimming was approached. Hundreds of these tools were found in the 1910 excavations of Machu Picchu (including the one I had the opportunity to see, in the photo below) as well as at many other Andean archaeological sites. Some even show the finger indentations used to grip the stones.

Hammerstone at Machu Picchu

Several types of fine masonry styles were used, based on the size and shape of the stone blocks. The most important structures, such as the curved wall of a temple at Machu Picchu in the photo below, were built using similar rows of smooth and roughly rectangular blocks. Other walls were composed of irregular shaped polygonal blocks that are fit together like a jigsaw puzzle. One famous cut block in a wall in Cusco has 12 sides, although blocks with even more angles are known. Many fine stone walls have a signature rounded or convex “pillowed’ shape along the block edges; this creates an artistic effect of light and shadow that accentuates the patterns of the walls and draws attention to the fine seams between the blocks.

Curved wall melded to bedrock at Machu Picchu

The close fits between adjacent blocks were achieved during construction by hoisting a block in and out of position to check the fit and then adjusting the shape as needed. Exactly how this was accomplished is a bit murky, especially for the gigantic blocks, but different types of template or scribing systems may have been used. Large temporary ramps were built with rock rubble to move the stone blocks upwards and into place. Disassembled ancient walls show that the closely fit joints at the front extend variable distances into the blocks, from only a few inches deep up to the entire thickness of the wall in extremely important structures. No mortar was used on the front faces of walls, although in some construction types rock rubble was used as fill behind the tightly fit front faces. While this process of shaping and tightly fitting heavy blocks together was clearly time consuming, it was not technically difficult

A characteristic feature of Inca stone walls is an inward slope of 3 to 5 degrees, and sometimes up to 10 degrees. This increases the resistance of the walls to the shaking of an earthquake and can support a very heavy roof load. The inward slope also helped to create a visual effect of an imposing and impenetrable structure.

Spectacular Sacsayhuaman and other Feats

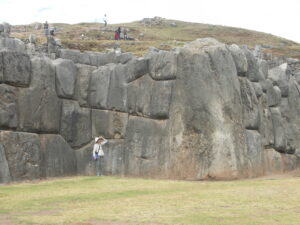

The grand architectural complex of Sacsayhuaman, constructed on a steep hill with an impressive view of Cusco and the surrounding valley, is one of the archaeological wonders of the Americas. On the north side of this site are three immense terrace walls formed by massive interlocked stone blocks constructed in a zig-zag pattern. These carved blocks are unmatched in size anywhere in the Americas. Some reach 13 feet in height and estimates of the weights of the largest blocks range up to almost 200 tons. The towering walls are approximately 18 feet high; the longest wall extends for about a quarter of a mile. Possibly more than at any other Inca archaeological site, the blocks at Sacsayhuaman have prompted wild theories that the walls were constructed either by a race of giants or by the Devil.

Terrace wall at Sacsayhuaman

Abundant evidence, however, indicates that Sacsayhuaman was constructed using only human labor. For an estimated 60 years, a labor force of perhaps 20,000 men worked under a state-organized labor tax service to build the extensive complex.

And what remains is only a small fraction of the stupendous monument that existed during the height of the Inca Empire. After the Spanish invaded the empire and secured their occupation of Sacsayhuaman, they began the process of having the stone structures dismantled as a convenient source of building materials. An early Spanish chronicler reported that virtually every Spanish home built in Cusco contained blocks from Sacsayhuaman. Additionally, rumors of the possibility of buried treasure within the complex encouraged destructive excavations. Today, only the largest stone blocks remain. Ironically, these were not carried away because they proved much too difficult to move.

Sacsayhuaman

The colors, characteristics and locations where stone blocks were obtained were clearly important to the Incas. The extremes that they could go to in sourcing appropriate rock are illustrated by shaped andesite blocks that were incorporated in an Inca center high in the Andes Mountains near modern Saraguro, Ecuador. Analyses indicate this andesite is from the same source used to construct many of the important structures in Cusco and was obtained from the Rumiqolqa quarry. Archaeologists consider this a transfer of sacredness that tied the new center to the homeland in Cusco. One detail that obviously didn’t deter the Incas – the Rumiquolqa quarry is located an incredible 1,000 miles from the site in Ecuador. Dragging those andesite blocks for all those long miles clearly required monumental efforts on the part of the workers.

PHOTOS

Quarry and temple wall at Machu Pichu, my photos, 2009

Hammerstone at Machu Pichu, photo by J.P. Torres, 2005

Sacsayhuaman megaliths, photos by F.H. Swan and me, 2009

If you like my posts, please scroll down to the bottom of this page and leave your email address on my website. You’ll receive messages only when I publish a new post (about once a week) and my occasional newsletter. Join now to stay up-to-date about geology, geography, culture, and history.

Another great article. Having spend several days in Sacsayhuaman I often wondered how those blocks were carved and transported. I ddi not release that some of the stones came such long distances.

Thanks John. Yes — Sacsayhuaman is such an amazing place! I think most of the really large blocks are limestone, which looks so sharp and rough to handle, besides weighing tens of tons. It is difficult to see how they could ever handle and fit the largest ones.

Great article! Building these sites must have required an incredible organization, planning and supervising too. Similar to building the pyramids, yet in mountaunous terrain. It would be interesting to see a map with the roads used to transport the blocks.

Thanks Kathelijne! Yes — the ancient Andeans were amazing engineers.

Amazing how much we were taught about Old World culture and how little we were taught about New World culture. Kinda like US history…

Agreed! Thanks, Steve!

I just happened along to your article. I spent a few days at Sacsayhuaman on two trips and have always been amazed by the stonework. As an engineer who has run large projects, I am awestruck. The organization, planning, and logistics complexities are on a par with the stonework. I am one of those who think this was a massive effort by a lot of people slowly splitting, dragging, chipping, and grinding the rock. Each aspect of the project from the quarry, food support, and the transport to the shaping and placement of the stone is very complex.

It is a tribute to human ingenuity and tenacity.

Thanks for this comment, Michael! I agree that immense efforts by thousands of people were required for these monumental constructions. The ancient ones left us with many awe-inspiring archaeological sites.

Has anyone anywhere been able to accurately reproduce the fitting of stones to the same degree of accuracy, even much smaller test stones, using these stone tools? Didn’t the Inca themselves say that the megalithic stones were not their work, and isn’t the work the Inca did with the colonial Spanish watching of a much inferior quality and using much less massive stones than the megalithic work?

The answer to your first question is yes. Check out the papers of Jean-Pierre Protzen — a pdf for one paper is here: https://online.ucpress.edu/jsah/article/44/2/161/57823/Inca-Quarrying-and-Stonecutting. Hammerstones were used in Protzen’s experiments, and as the abstract for his paper notes: “Experiments show that with this process stones can be mined, cut, dressed, and fit with little effort and in a short time.” As for what the Incas did or did not say, that gets very murky! There are, of course, no records written by the Incas, and translations and interpretations by the Spanish who interacted with the Incas aren’t necessarily reliable. As for colonial construction, the Spanish had objectives and standards that were quite different from those of the Incas.

Great article Roseanne, and sober thoughts. No need for laser guns or antigravity devices. Hard work and basic tools did it.

Thanks for your comment, Peter.

A very great post, thank you very much!

Do you know why the stones are often much smaller at the top than at the bottom? As if someone else put them on top?

I’ve noticed this with other Inca walls as well.

Some claim that the stones were made by an older culture and then the Incas built on top of them, what do you think? 🙂

Thanks for the answer!

Thanks for the comment, Rudolph. From what I have learned, almost all the Inca walls were built by the Incas (rarely, they may have added onto structures built by earlier Andean cultures). Larger blocks were probably used at the bases of walls for stability, plus adding smaller blocks higher on the walls would have been easier to put into place.

are you guys retarded no way a million men could move 10000lbs rocks into shape like that clearly advanced civilization with technology not of this world did that

Hmmm. Your skepticism aside, what solid evidence is available for a civilization with “technology not of this world”? I sure don’t know of any. IMO, the reports of 16th century Spanish chroniclers, who actually watched the Inca builders in action, along with unfinished Inca construction projects that are in various stages of completion, provide compelling evidence that they had the time and manpower to complete monumental constructions.

With the greatest respect, and speaking as an unqualified observer, even the most authoritative views on ancient constructions tend to circularity: ‘We know who the builders were, the stones are enormous, they are super-precise in cut and contiguity, we cannot absolutely explain and could not now easily reproduce the placement and fitting of them, they must have used known methods plus, in difficult cases, some unknown methods, there are striking differences in quality and aesthetic which can only be explained by supposition restricted to what we know about the builders… because we know who they were.’ Thus run the arguments, or so it seems to this amateur – only an uninformed opinion!

Thanks, Peter. I’m a geologist and not an archaeologist, but from my research, many different types of data typically go into robust assessments of who did what – and when and how.

Hi Roseanne, like Daniel R Clark above, I think you are deluded if you think the Inca’s carved out, transported and built these megalithic walls and buildings using the primitive tools at their disposal.

No only do we see these megalithic in Peru, but all around the world in Egypt, Japan, Easter island, the list goes on and on….. and as for your reasoning behind using smaller stones on top that’s ridiculous… again around the world there are many examples of walls that are still complete and intact….. proving that repairs were made by people’s with inferior skills, tools and knowledge.

Surely you can’t just ignore the fact that, like with the pyramids, the evidence is there that building skills and techniques deteriorated…. Why was that ? I’ll explain…. Because these cultures never had those skills in the first place… They just came across, or were led to, these abandoned megalithic sites and decided to inhabit them.

Thanks, Tony. I’m a strong believer in data, and those sources I describe in my post are convincing to me, as well as many others.

Please direct me to the source that says that blocks greater than 50 tons were “dragged” over 1000 miles. If the land in between was a slippery surface downhill all the way it might be feasible but obviously it is not. My BS detector’s siren is blaring right now.

This is the source I used (probably there are others): Dennis Ogburn, “Power in stone: The long-distance movement of building blocks in the Inca Empire,” Ethnohistory 51, no. 1 (2004): 101-135. At least 450 blocks weighing up to about 1,543 lbs, or 700 kg, were transported, probably by thousands of men carrying each stone on a litter. Of course, no one really knows how the stones were transported — but since they are present 1,000 miles from where they were quarried, and the Incas are renowned for their monumental achievements, what is a better explanation?

1) The polygonal walls in Peru share the same characteristics as those seen across the globe (Egypt, Easter Island, Turkey, etc). The probability is low that the Incas just happened to make the same kind of difficult walls, employing the same kind of bedding joints, “Utah” stones, and nubs despite being separated by thousands of miles and thousands of years.

2) The Inca architecture style is blatantly obvious. It consists of small rocks and adobe. It can be seen on top of the precision polygonal walls or within repairs of the precision polygonal walls. This is not to knock the Incas. Today, the financial strain would be too great to make such impressive walls. The fact remains, there are 2 distinct styles that show 2 distinct levels of technology.

3) The article you reference as proof that such precision walls are possible with pounding stones does not, in fact, demonstrate this. They provide 1 picture of a stone block sitting on another stone block with no context. Only one crude joint was semi- accomplished.

For reference, MIT did a project they called Cyclopean Cannibalism. They produced a small block wall made from discarded concrete and stone. Despite using computer guided saws, and 6 axis radial arm equipment, rotary tables, stone milling equipment, the joints seen on the wall are not, by a considerably degree, on the level of the walls of ancient Peru.

I’ll end with saying that when I was a young undergrad in Anthropology, I believed this pseudo-science that primitive civilizations made the most amazing, durable, and impressive walls using primitive means. As a contractor who regularly fabricates stone, I know this is malarkey.

Thanks for the comment, Joe. The Incas built a large number of monumental structures, with a wide variety of masonry techniques displayed in the walls. There is abundant evidence that they used hammerstones to shape blocks, because hundreds of these have been found near construction sites. (At least one example that I recall was a hammerstone enclosed within a wall, where a laborer evidently left it behind.) And — I’m not an archaeologist, but from what I have read, it makes sense that ancient people came up with similar engineering solutions for their projects – afterall, they were using similar materials, simple tools, etc. Other than a belief that such precise masonry couldn’t possibly be made by ancient people and technologies, what clear evidence is there for an alternative? None that has convinced me.

When you make assertions like “a labor force of perhaps 20,000 men worked under a state-organized labor tax service to build the extensive complex” begs the question “You have evidence of this state-sponsored tax system”? And it spanned at least 3 or 4 generations of people. Really? This is evidence to you. It is supposition and fantasy in my books.

I have looked at you suppositions, and all trials to replicate these works with neolithic technology fail to replicate this type of work or even come close. Dream on partner!

The mandatory mit’a labor system used by the Incas is an established fact, documented by Spanish colonialists. Similarly, Spanish chroniclers recorded many of the construction techniques of the Incas, including the use of temporary ramps that allowed stone blocks to be moved up and placed in high positions on walls. The number of workers in the labor force for Sacsayhuaman is, of course, an estimate by archaologists. The Incas left behind numerous and varied extemely sophisticated construction projects — they should not be underestimated!

So many myths and POVs surround these ruins. The Incan masons have proven their stonework capabilities elsewhere and should be given the benefit of doubt here since contrary evidence is hearsay.

As a quarryman-stonemason I have definite opinions on practical methods and processes they would have used and would argue that their design choices are foremost pragmatic and indicative of the local area’s geology.

Good to hear — thank you for your comment.