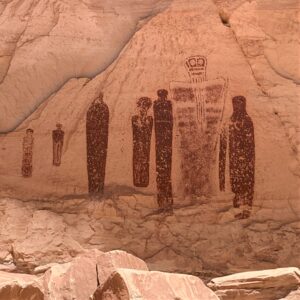

Masked faces on ancient life-sized, mummy-like figures form a long line on the rock wall of a shallow alcove in a remote part of Canyonlands National Park in southern Utah. Known as the Great Gallery, the 200-foot-long (61 m) panel contains around 20 eerie looking triangular-shaped bodies with small heads. Many of these anthropomorphic figures have round bulging eyes and elaborate decorations, and some figures are 7 feet (2.1 m) and taller. At least one thousand years old, and possibly much older, these images likely played a part in ancient rituals held deep in the canyon. Today, many researchers consider them among the finest examples of rock art in the Americas.

Pictographs and Petroglyphs

A bewildering collection of geometric, animal and human figures can be found in ancient rock art on the Colorado Plateau in the southwestern United States. Ancient artists have used the rock surfaces of canyon walls and boulders as drawing boards and canvases for rock paintings, or pictographs; they created petroglyphs by pecking, chipping, or cutting away the rock surface.

Anthropologists who study these forms have divided the art into styles that follow geographic and cultural boundaries. The supernatural appearing human-like images in the Great Gallery are known as Barrier Canyon Style, first described by Polly Schaafsma from the Horseshoe Canyon site (formerly known as Barrier Canyon). The National Park Service established the Horseshoe Canyon unit of Canyonlands NP in 1971 to protect this spectacular rock art. We can find the art style throughout much of eastern Utah and into northern Colorado.

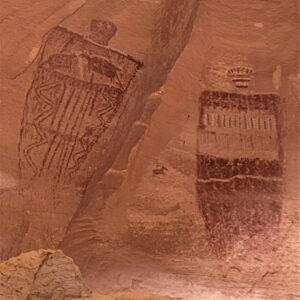

Barrier Canyon Style includes both rock paintings and pecked petroglyphs, sometimes with combinations where painted figures have petroglyph eyes and body decorations. For some paintings, the cream-colored sandstone was ground smooth to prepare the surface for paint. Paintings are typically red, but shades of blue, white, yellow and black are also used. Ground minerals, including iron for the reds and charcoal for black, provided pigments. To make the paint, a binder such as plant or animal oil was added so the paint would adhere to the rock surface. The artists used several layers of paint in some of the Great Gallery images.

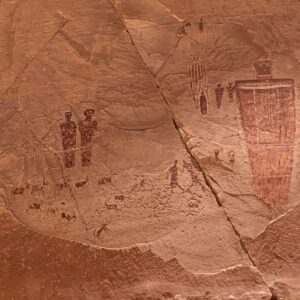

Since I am especially fond of animals, my favorite figure is the one above on the left with the two animals displayed on the chest. The complex stripes, zigzags and other geometric patterns on both of the figures are also intriguing. The colored paint has faded over the centuries, although it was probably vivid when first painted. Another of my favorite scenes shows small human images with bighorn sheep, below.

When, Where and Why

When was the Great Gallery painted? Researchers have sought the answer to that question for decades. Estimates range back in time for several thousands of years, but with high uncertainty, as direct assessments of rock art dates typically are difficult to make. (An interesting problem, which I plan to research for a future blog post!) Recently developed age dating techniques applied to a rockfall that removed some of the art (visible on the left side of the photo below) indicate a time window between 1 to 1,100 CE when the paintings could have been made (Pederson et al, 2014). This is younger than many previous estimates.

The Great Gallery requires extra effort to reach. It is located east of Highway 24 north of Hanksville, Utah near the spectacular rock formations of the San Rafael Swell. A bone-jarring ride on 32 miles (51 km) of unpaved roads ends at the trailhead. Then, there is a 3+ mile hike beginning with a steep descent into Horseshoe Canyon and a long slog, much of it in loose sand, along the stream wash to reach the Gallery. I recently visited this site for the second time, and it was as memorable as my first visit almost a decade ago.

Rock art is an important form of cultural expression. What were the ancient artists thinking when they laboriously painted and pecked these figures on the rock canvas? We have an incomplete understanding of the dreams, religions, and traditions of indigenous people. The rocks can’t speak, so we will never know what this artwork truly represents.

Please share this post! Also, please scroll down to the bottom of this page and leave your email address on my website. You’ll receive messages only when I publish a new post (about once a week) and my occasional newsletter. Join now to learn more about geology, geography, culture, and history.

SOURCES

Cole, S.J., 1990. Legacy on stone: rock art of the Colorado Plateau and Four Corners Region. Johnson Books.

Pederson, J.L., Chapot, M.S., Simms, S.R., Sohbati, R., Rittenour, T.M., Murray, A.S. and Cox, G., 2014. Age of Barrier Canyon-style rock art constrained by cross-cutting relations and luminescence dating techniques. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 111 (36), pp.12986-12991.

Schaafsma, P., 1980, Indian Rock Art of the Southwest. School of American Research and University of New Mexico Press.

All photos are mine; May 2021

Thanks, Rosanne,

Another interesting article. I love the otherworldly nature of the Barrier Canyon petroglyphs.

There are some interesting panels along the San Juan river as well, although a mix of styles.

I appreciate your writing, photos and sense of adventure.

Thanks again,

Larry Mallery

Thanks so much Larry! I appreciate your note. And — I hope to see more Barrier Canyon Style art; so fascinating!

This is very interesting, Roseanne.

Thank you once again. You’re nudging me

in the direction of my hiking boots and my bucket list is growing.

I’m building strength and endurance and setting goals to go to places you’ve described.

Eden

Good to hear, Eden! Thanks for the note. The Southwest definitely has many great places to explore!

Good stuff, Roseanne.

I’ve personally spent a lot of time in the San Rafael Swell area in Utah. There is a panel located in a place called Buckhorn Wash that has some curious markings that I have not seen elsewhere among the catalogue of Barrier Canyon Style pictographs. It seems to me that it is a map of the canyon when compared to satellite imagery. I haven’t seen any mention of this particular detail anywhere and you look like you know a whole lot about this kind of stuff so I’d really like your opinion!

If you have some time I’d really appreciate if you could take a look at some photos and tell me what you think. Thank you!

Good to hear that you like this post! I am definitely not an expert on rock art, but I would like to see your photos. Thanks!