World Heritage Site designations provide protections for sites having outstanding cultural and natural heritage. Safeguarding ancient Egyptian cultural treasures that the filling of the Aswan High Dam would inundate laid the groundwork for this program back in the 1960s. At that time, UNESCO (the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) headed a campaign to salvage artifacts from the rising waters of the Nile River. Besides the excavation and detailed recording of hundreds of ancient sites, crews moved two enormous temples to higher ground. Today these comprise the site of Abu Simbel, named for the nearby town.

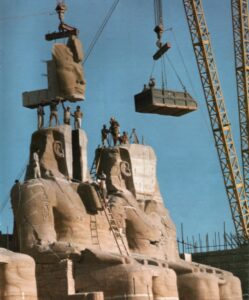

Relocating statues of Pharaoh Ramesses II as part of a temple at Abu Simbel (1967, Wikipedia)

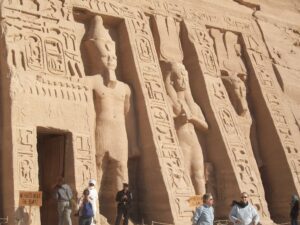

The temples at Abu Simbel were originally carved into a cliff of reddish sandstone by Egyptian sculptors about 1300 BCE. They are a monument to Pharaoh Ramesses II, commemorating his victory in an important battle against the Hiitite Empire. The largest temple contains four massive statues of the pharaoh that are about 66 feet (20 m) tall. The Egyptians dedicated the smaller temple to Ramesses’ wife, Nefertari, and the goddess Hathor, the sky deity that was the symbolic mother of the pharaohs. There are a series of statues about 33 feet (10 m) high, including two of Ramesses II. Artists carved the interior walls of the temples with elaborate and colorful scenes.

A few decades ago, I worked in Egypt for several months, and had the good fortune of visiting monumental Abu Simbel — extremely impressive! As part of my three trips to Egypt, where colleagues and I were evaluating earthquake hazards for the Aswan High Dam, we visited many other fabulous archaeological sites on day trips or when traveling through Cairo. From the pyramids at Giza to the ancient city of Thebes and the Valley of the Kings, to Abu Simbel and other ruins saved from the waters of Lake Nasser, UNESCO has granted World Heritage Site designations for these places. Amazing sights—particularly for me (officials stamped my empty passport for the first time only when this work brought me to Egypt)! The trips were the beginning of my appreciation for the many other special places worldwide recognized as UNESCO World Heritage Sites — and I hope to visit many more during my lifetime.

Temple of Nefertari at Abu Simbel (2009, Wikipedia)

Amazing Peru

The UNESCO World Heritage Site designations are intended to conserve for posterity those sites that signify a remarkable accomplishment of humanity, or a place of great natural beauty. In Peru, there are eight sites that protect extraordinary archaeological resources and meet cultural importance selection criteria. I’ve visited several of these sites, and I’ve described some of them in my blog posts, based on research for my book, The Monumental Andes. The sites and the year of listing as a World Heritage Site (in parentheses) are:

City of Cusco (1983) — capital city and center of the universe of the Inca Empire, beginning around 1400 CE; after European influences reached the Andes in the early 1500s, this empire collapsed, and Spanish colonialists directed the construction of Baroque churches and buildings over the foundations of former Inca palaces and temples in Cusco.

Machu Picchu (1983)—city on an isolated and narrow ridge top to the northwest of Cusco, built as a royal Inca retreat; the building challenges on this steep site, and the success of the Incas in meeting these with excellent engineering and construction techniques, are truly remarkable.

Machu Picchu (2015, Wikipedia)

Chavin de Huantar (1985)—a major ceremonial center with a temple complex of cut stone blocks in a high mountain valley in northern Peru; built by the Chavin culture that flourished between about 1200 and 500 BCE, the site is subject to frequent floods and landslides, but was close to two rivers that were likely considered an important source of power.

Chan Chan (1986) – capital city of the Chimu culture and one of the largest mud-brick (adobe) architecture settlements in the world; the city on the arid north coast of Peru contained at least ten monumental palaces built for a series of kings who reigned over hundreds of years until 1470, when the Incas conquered the Chimu.

Mud-brick (adobe) walls at Chan Chan (2007, Wikipedia)

Lines and Geoglyphs of Nazca and Pampas de Jumana (1994) – enormous geometric shapes and animal designs scraped onto the surface of the Nazca Desert in southern Peru by the Nazca culture between about 100 BCE and 700 CE.

City of Caral-Supe (2009) -a large site that was part of the sophisticated Norte Chico civilization that built extensive settlements along the north coast of modern Peru beginning about 5,000 years ago.

Qhapaq Nan/Great Inca Road (2014) – a system of roads and trails spanning over 3,700 miles (6,000 km), engineered by the Incas, who connected many routes that were established by their ancestors; major roads extended north to south along the spine of the Andes Mountains and the Pacific coast, and west to east from the coast to the jungles of the Amazon Basin; today remnants of the system extend from Colombia, across Ecuador, Peru, and Bolivia, and into Chile and Argentina.

Chankillo Archaeoastronomical Complex (2021) – a set of constructions that used the sun to indicate the solstices, equinoxes, and dates of the year with a precision of 1 to 2 days; the site is on the north coast of Peru and built between about 250 and 200 BCE

Information about Cusco, Machu Picchu, Chavin, and the Great Inca Road is in many of my blog posts – and there will be much more on these and other impressive archaeological sites in my book once it is published! (The keyword search on my blog page will be helpful if you want to find the blog posts.)

Conservation Challenge

World Heritage Sites are governed by a countries’ own laws and finances. UNESCO offers technical assistance and professional training, plus under certain conditions, funding to facilitate conservation efforts. Typically, the international recognition of a site benefits local populations with increased tourism revenue.

Protection for posterity cannot be guaranteed, of course. UNESCO has also established a “List of World Heritage in Danger”, with objectives of encouraging a country to implement measures to counteract the threats and to increase international awareness. For the site of Chan Chan in Peru, UNESCO officials placed the archaeological site on the Danger list at the same time they added it to the World Heritage Site list, as rain and wind are eroding and damaging the earthen structures.

Pelicans carved into adobe blocks at Chan Chan (2004, Wikipedia)

Many modern societal problems, led by population growth and global warming, threaten several dozen World Heritage Sites. Specific reasons that lead to environmental degradation range from military conflict and civil disturbance (affects sites in multiple countries including Syria, Iraq, Yemen, and several African countries), to pollution from agricultural runoff, deforestation from illegal logging, poaching, encroaching roads, drug trafficking, mineral exploration and extraction, lack of maintenance, and on and on.

Sometimes, the UNESCO Danger listing has sparked conservation efforts and officials subsequently remove the site from this list. Among these are the Galapagos Islands in South America, where concerns included introduced plants and animals that were decimating native species until an eradication plan helped to control this problem. Another was Yellowstone National Park, where wildlife management issues and water quality problems such as sewage leakage in parts of the park needed to be mitigated. Conversely, to date, UNESCO has deleted three sites from the World Heritage Sites list. For two of these, the character of each site became significantly changed by construction of massive modern structures. In the third case, a wildlife reserve, poaching and habitat destruction eliminated almost all the animals; then, oil was discovered, prompting the country to reduce the reserve size by 90%. (Not a conservation success story!) This led to UNESCO deleting the reserve from the World Heritage Site register.

Today worldwide there are about 1,154 World Heritage Sites found in 167 countries. I hope to travel in Peru again to see the ones I’ve missed, as well as to visit many more of these sites in other countries. So much to see—so little time!

Geoglyph of hummingbird in the Nazca Desert, Peru (2003, Wikipedia)

If you liked this post, please share it and/or leave a comment or question below and I will reply – thanks! And if you’d like to receive a message when I publish a new post, scroll down to the bottom of this page and leave your email address on my website. Join now to learn more about geology, geography, culture, and history.

SOURCES

Information primarily from Wikipedia

Photo of reconstruction of Abu Simbel temple, 1967; façade is 108 ft (33 m) high and 125 ft (38 m) wide, by Per-Olow Anderson. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Abusimbel.jpg

Photo of Temple of Nefertari at Abu Simbel, 2009, by Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Temple_to_Nefertari_at_Abu_Simbel_(IV).jpg

Photo of Machu Picchu, 2015, by W. Bulach https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:00_1596_Ruinenstadt_Machu_Picchu.jpg

Photo of adobe walls at Chan Chan, 2007, by Jim Williams. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Chan_Chan_Archaeological_Zone-110903.jpg

Photo of pelican carvings in adobe at Chan Chan, 2004, by J. Stander https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a6/Chanchan_pelicans_detail.JPG

Photo of hummingbird, part of the Nazca Lines in Peru, 2003, by Bjarte Sorensen https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Nazca_colibri.jpg

Leave A Comment