Hundreds of years before the Inca Empire rose to fame and glory, the Tiwanaku culture flourished in cold and thin air in the Andes Mountains. The capital city of this culture, also known as Tiwanaku, is at an elevation of about 12,800 feet in the region south of Lake Titicaca, now in Bolivia. Tiwanaku began to emerge as a major ritual and political center around 250 CE. By sometime around 500 CE the city had substantially expanded, attracting many pilgrims, and had become an important trade center. The Tiwanaku people unified a large area of the central Andes through a shared religion and cultural practices, using an economic system that included extensive trade routes and llama caravans. Monumental temple construction, exquisite artistic creations, intensive agricultural practices, and many other accomplishments of this culture provided a foundation for the Andean societies that followed.

Map of Lake Titicaca showing Tiwanaku in lower right corner

Sandstone

Collecting and transporting heavy stone blocks from distant quarries were among the many impressive accomplishments of the Tiwanaku people. A reddish sandstone was used in some of the massive temples built in the capital city, and this rock has been traced to mountains about 10 miles south of the city. There, naturally occurring joints in the rock were utilized by the ancient quarry workers to simplify the task of carving out large blocks. Hundreds of blocks are found that were moved from their original locations by quarry workers while sorting them into those deemed useable and those that were not. Ground surfaces are littered with sandstone flakes, indicating that blocks were trimmed on-site into the desired rough rectangular shapes.

The Sunken temple at Tiwanaku

Moving blocks of stone that could weigh tens of tons isn’t simple. Wheels were not used by ancient Andeans, probably because wheels are less useful on rough terrain, and due to the lack of oxen, horses, elephants, or other strong draft animals. Clues on how the sandstone blocks were moved comes from many of the heavy blocks abandoned along the road that heads northward from the sandstone quarry towards Tiwanaku. There are either 2 or 4 divets carved into the edges of many of these blocks. Located about 4 to 6 inches below the top of a block on opposing edges, and about 3 to 4 inches wide, they have been named “rope holds”. They indicate that the ancient people used strong fiber ropes to laboriously move each block from the quarry across the 10 miles or so to the Tiwanaku destination.

To reduce friction on the road surface, beds of rounded pebbles may have been used, or mud placed to lubricate the track. Other blocks may have been pulled along on beds of wooden logs, with the logs at the back of the block picked up in sequence and moved forward by workers. Some shaped blocks show substantial scraping, indicating they were dragged directly across the ground surface.

Andesite

As the power and influence of Tiwanaku’s realm expanded, another major civic building program began around 500 to 600 CE, in which existing buildings were razed or substantially renovated, and large new ones erected. The hard volcanic rock andesite became an important material for these structures. Andesite was incoporated in new construction for important architectural elements, especially for visible public facades and communal public spaces. At some temples there is evidence that sandstone blocks were removed and replaced by andesite blocks. Most impressive is a single massive block of andesite elaborately carved to form the Gate of the Sun, which measures about 9 feet high and 12 feet wide.

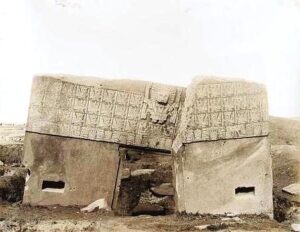

Temple of the Sun in a 1903 photo

Andesite is much heavier and harder to work than sandstone, so the value of this stonework must have been significant. Archaeologists interpret the distinctive blue-gray of the andesite as a symbol of the newly incorporated landscapes, communities, and sacred places that came under the influence of Tiwanaku.

Researchers seeking to identify the andesite quarry were mystified for decades, in part because numerous outcrops of volcanic rock occur in this region of the Andes. Also, the mineralogical and chemical compositions of volcanic rocks can vary widely during eruptions, making clear “signatures” of origin difficult. One valuable clue was available. To the north of Tiwanaku near Lake Wiñaymarka, one of the two lakes that compose Lake Titicaca, abandoned large and roughly trimmed rectangular andesite blocks are found on the shoreline of the lake. More “sofa-sized” blocks are across the lake in the foothills of a prominent volcanic peak named Mount Khapia, southwest of Yunguyu near Copacabana.

Recent chemical analyses of possible volcanic rock sources, combined with samples from architectural stones and carved monoliths at Tiwanaku, indicate the primary source of the andesite was the slopes of Mount Khapia on the western shore of Lake Wiñaymarka (Lake Huanamarca on map above). As the puzzle pieces of this story fell into place, it became clear that the andesite blocks were quarried and roughly shaped, and then loaded onto rafts made from locally harvested totora reeds and transported about 14 miles across the lake.

Lake Wiñaymarka with Mount Khapia on the left side

Transporting huge and heavy, multi-ton stone blocks on reed rafts seems almost impossible, nontheless it appears that is the case. (Boats have been built from totora reeds for millenia, and even today are used for the famous floating islands of the Uros people on Lake Titicaca — still, the size of the stone blocks makes this seem incredible.) What propelled these rafts – were sails used, or oars? Did any of the rafts sink or the contents fall out, leaving the rectangular blocks on the bottom of the lake? Clearly, this was an ambitious undertaking that required substantial engineering skill. It would be an intriguing topic for experimental archaeology, although I have found nothing specific about this in the literature to date.

The raft trip across Lake Wiñaymarka was only one leg of the trip. A town named Iwawe, located where the Tiwanaku River enters Lake Titicaca, was used as the port where the andesite blocks were delivered. The blocks were then hauled overland, using thick ropes and human muscle power, for the 14 miles or so to Tiwanaku. Quite a journey.

One more puzzle piece fits neatly into this picture. In a late renovation phase, the monumental Kalasasaya platform was fitted with an addition that included a series of 11 andesite pillars along the west side of the temple complex. These megaliths, each 13 feet tall and carved from a single piece of stone, were arranged so that at the time of the austral summer solstice (December 21), the sun set over the southern-most pillar. On the austral winter solstice (June 21), the sun set over the northern most pillar — and simultaneously, over the peak of Mount Khapia, the source of the andesite rock. The ancient Andeans excelled at melding nature and their sacred structures.

The Sunken temple with view towards the Kalasasaya at Tiwanaku

The Ruins of an Ancient City

For more than 500 years the Tiwanaku culture prospered – a remarkably long time. The decline began around 1000 CE; within another hundred years only wind and silt were blowing through the abandoned spaces of the capital city. The once-cohesive society appears to have been broken down into conflicting factions, most likely because of both social and ecological factors, especially resource competition. Uprisings by the local people are apparent, in which elite residences, megalithic monuments and many of the large doorways in Tiwanaku were vandalized. A major drought beginning roughly around 1100 CE, dealt a final death blow to this culture.

Since the city of Tiwanaku was abandoned 1,000 years ago, many of the monumental ruins have been demolished by local residents and travelers to the region. For centuries, the carved stone blocks from the temples were carted away as conveniently pre-cut building stone to construct the churches, residences, tombs and mills in nearby towns and the Bolivian capital of La Paz, about 50 miles away. Legends of hidden gold and silver contributed to the site’s destruction as looters dug through the ruins seeking treasure. Monumental walls and statues are riddled with bullet holes from target practices by military personnel. Stone blocks were broken up to provide foundation material for a Bolivian railroad that passes nearby.

Only a small part of the more than two square mile area of Tiwanaku has been excavated by archaeologists. Some of this, especially excavations and reconstructions conducted in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, were amateurish work that increased the confusing jumble of structural stones and artifacts. Given that the Tiwanaku people did not have a written language, and after such sustained destruction, information about this society is as fragmentary as the cultural remains that have survived. Nonetheless, those remnants provide a fascinating picture of the proud Tiwanaku people and their majestic capital city.

PHOTOS

Map of Lake Titicaca; es:Usuario:Haylli, based on map from http://www.aquarius.geomar.de / CC BY-SA (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/)

Reconstruction of Sunken temple at Tiwanaku; Dr. Eugen Lehle / CC BY-SA (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0) https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tiwanaku_-_Versunkener_Hof.jpg

Gateway of the Sun in 1903: By Arthur Posnansky – https://web.archive.org/web/20160304081226/Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien, Bilddatenbank., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=24862061

Satellite view of Wiñaymarka Lake, the southern sub-basin of Lake Titicaca, and the mountain Khapia; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Khapia#/media/File:Lago_Menor_o_Hui%C3%B1amarca_Per%C3%BA_Bolivia_Satelital_map_68.85829W_16.png

Semi-underground temple and Kalasasaya in the background: By Pavel Špindler, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=55228080https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tiwanaku#/media/File:Templo_de_Kalasasaya_a_socha_Monolito_Ponce_-_Tiwanaku_-_panoramio_(1).jpg

If you like my posts, please scroll down to the bottom of this page and leave your email address on my website. You’ll receive messages only when I publish a new post (about once a week) and my occasional newsletter. Join now to stay up-to-date about geology, geography, culture, and history.

Roseanne, I have been following your adventures and wonderful descriptions and

explanations of the cultures and their building materials and methods.

THANK YOU

Eden

Thanks Eden! Wow — great to hear from you! So good to hear that you like my posts – thanks again.

Great post, Roseanne. Those must have been very strong ropes — imagine when one snapped and 500 men went sprawling all over the road. And I’ve often wondered about rolling rocks and rolling logs — was the wheel have invented dozens of times all over the world? That’s not the mythology.

Thanks Steve! Yes — a Spanish eyewitness report from the late 16th century described the ropes used for bridges to be “as thick as a man’s body or thicker”. Also, ancient Andeans definitely knew about wheels — for example, 2,000 years ago the Nazca people used turntables to revolve ceramic pots so that they could be decorated evenly on all sides.

Roseanne, your site is inspiring, the most exciting of all geological/cultural resources. Ready to travel!

Great to hear – thanks, Rich! I certainly have a long list of places I’d like to travel, including return trips to many destinations that I especially appreciated!