The archaeological site of Chavín de Huántar, high in the Andes Mountains of northern Peru, was the seat of an important religious power and cult that flourished for hundreds of years, beginning about 3,000 years ago. Shamanic beliefs and practices apparently played a central role in this religion, with some individuals using hallucinogenic drugs to reach altered states of consciousness for interactions with the spirit world. Exotic and somewhat sinister art forms, recognized as an essential part of the religion, depict these transformations.

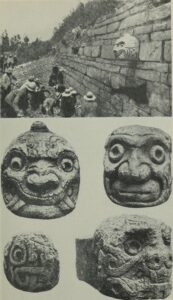

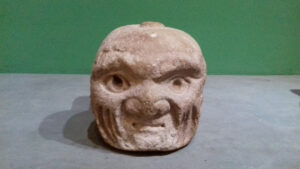

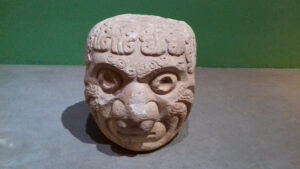

Among the most notable: fearsome large heads carved from stone that projected out from the exterior walls of the monumental Chavín temple complex. Called tenon heads, or pegged heads, more than forty of these over-life-sized carvings were originally installed. Arranged in a series, they dramatically document the shamanic transformation of a human into supernatural animal spirits. Almond-shaped human eyes give way to round and bulging eyes, grimaces depict the nausea that accompanies transformation, mucus streams out of noses in the nasal irritation associated with use of hallucinogenic snuff, and near the end of the sequence, heads display prominent fangs and swirling snakes for hair.

The use of hallucinogenic drugs was important in many ancient Andean cultures, as well as numerous other indigenous cultures in the Americas. San Pedro cactus, which contains mescaline, grows in the vicinity of the Chavín de Huántar site. This well-known hallucinogen was apparently used by some of the Chavín people, and it is depicted in Chavín art. The religious specialists, however, likely used more powerful snuff from the seeds of the Andean tree Vilca or Wilca (from the Quechua word meaning “sacred”; genus Anadenanthera.) Abundant artifacts found at Chavín — including small mortars with the tops carved into the forms of jaguars and eagles, plus bone trays, spatulas, spoons and tubes – all provide evidence of hallucinogenic snuff rituals.

To follow the progression of transformation depicted by the tenon heads, viewers would have needed to completely encircle the large temple — one of many dramatic scenes arranged by the Chavín creators. (Another was eerie acoustic effects from the roar of water in drainage channels beneath the temple complex – the topic of my recent post: “Water and Power at Chavín de Huántar”.) Today only a single tenon head remains in its original position high on the temple wall; other tenon heads are in museums locally and in Lima, but most have been lost. Those heads that remain provide haunting and fascinating glimpses into the lives of ancient people and their pursuits to understand and perhaps influence the spiritual worlds.

I remember visiting Chavan, and wish I had read your piece about the heads. The progression from person to spirit animal is usually recorded orally, or in song. Fascinating to have it engraved in stone. Also the same in San Augustin, Colombia, where the goofy-looking stone heads have their cheeks stuffed with either mushrooms or marijuana.

Thanks Cathy. Nice that you were there — and also saw similar stone carvings in Columbia.

What a startling record preserved in stone no less. We children of the SIXTIES thought we had some corner on psychedelic drugs, but these guys had already beaten us to that punch by MILLENNIA!

Thanks Diana! Yes — a very good point!