Forty years ago, Mount St Helens exploded in a major volcanic eruption. Although this volcano has been quiet recently, it is considered active and could stir back to life anytime. Many other volcanoes in the Pacific Northwest are also active, with swarms of small earthquakes and occasional releases of steam indicating unrest deep underground. The 1980 eruption of Mount St Helens provided scientists with a tremendous amount of valuable new data, helping to shed light on volcano behavior throughout the region. Despite this information, no one knows where or when the next eruption will occur.

Mount St Helens, Mount Rainer, Mount Hood and many other volcanoes are part of a long chain of mountains that extend south from British Columbia, ending with Mount Shasta and the Lassen volcanic center in Northern California. Known as the Cascade Volcanic Arc, these volcanoes formed above the subduction zone between the North American tectonic plate and the Juan de Fuca, Explorer and Gorda tectonic plates. The small plates are fragments of the once enormous Farallon plate that was subducting beneath North America up until about 25 million years ago. At that time, the central part of the Farallon plate disappeared into the subduction zone and was replaced by the Pacific plate. Volcanoes in the Cascades today developed largely within the past 2 million years, with hundreds of eruptions during the last 1 million years, although volcanic activity has been happening in this region for about 37 million years. Currently the northern part of the volcanic arc in British Columbia is quiet, and the central and southern parts are showing the greatest amount of unrest.

Hazard and Risk

Erupting volcanoes present hazards to people and their infrastructure, but the degree of risk increases dramatically in densely populated areas. Today, millions of people in the Pacific Northwest live near volcanoes that are potentially active. In 2018 the US Geological Survey released a list of the most potentially dangerous volcanoes in the US. The rankings are not forecasts of which volcanoes are likely to erupt next, but they indicate the potential severity of impacts that could result from a future eruption at a given volcano. In assigning rankings that range from very low threat to very high threat, the scientists considered factors including recent activity level, eruption frequency, volcano type and explosive potential, and the density of the nearby population.

Out of a total of 161 volcanoes ranked in the USGS study, 18 were assigned a very high risk. Eight of these 18 volcanoes are in Washington and Oregon. Kilauea in Hawaii, which had lava creeping downhill and engulfing houses in flames as the report was being written, earned the #1 highest risk spot. The volcanoes in Oregon and Washington and their ranks are as follows:

# 2 Mount St. Helens, Washington

#3 Mount Rainier, Washington

#6 Mount Hood, Oregon

#7 Three Sisters, Oregon

#13 Newberry Volcano, Oregon

#14 Mt Baker, Washington

#15 Glacier Peak, Washington

#17 Crater Lake, Oregon

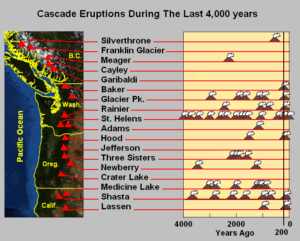

The chart below indicates the frequency of eruptions during the past 4,000 years for the various volcanic centers in the Cascade Volcanic Arc. The high recurrence rates and recency of some of the volcanic centers is quite interesting (and IMO – a bit disconcerting!)

Monitoring

The USGS operates the Cascade Volcano Center to monitor volcanoes in Washington, Oregon, and Idaho, as well as to conduct research on many aspects of volcanism. Natural precursors of eruptions include swarms of small earthquakes, increases in volcanic gas emissions and temperatures, and subtle changes that deform the shape of the volcano. Hazard maps prepared for high risk volcanoes include estimates of the extent of lava flows, ash and tephra falls (rock fragments forcibly ejected from a volcano), pyroclastic flows (chaotic and fast-moving mixtures of rock fragments, ash and gas) and lahars (volcanic mudflows or debris flows of rock debris mixed with water.)

The cloaks of ice and snow on Cascade volcanoes contribute significantly to eruption hazards, as high temperatures melt water that fuels fast moving lahars, These volcanic mudflows can flow for many miles down valleys, burying the landscape in thick layers of cement-like sediments. As the population has expanded around major metropolitan centers, developments have been built on top of the lahar deposits erupted within the past few thousand years.

The Top 4 in the PNW

USGS places the four volcanoes below in the top ten of the very highest risk volcanoes in the US.

Mount St Helens is the most active volcano in the Cascades and is probably the most likely volcano to erupt again in the near future. Forty years ago, the first warning signs that Mount St Helens would erupt began in March 1980, with a series of small earthquakes, followed by small eruptions and an ominous growing bulge on the north flank of the mountain. On May 18, 1980, a magnitude 5.1 earthquake triggered a major landslide of the weakened rocks over the bulge of magma, and the release of confining pressure inititiated a series of powerful eruptions that lasted for about 9 hours (photo below). An early blast of hot debris completely devastated a 230 square mile area, within minutes extinguishing all the life in what had been dense forest. The landslide on the north side traveled as far as 14 miles; the eruption cloud reached 15 miles high. At least 57 people lost their lives. Mount St Helens showed more signs of life between 2004 and 2008, with numerous small earthquakes, releases of steam, and magma extruded into the large crater at the summit of the volcano. Since then the volcano has been quiet – but scientists are closely monitoring it, as activity could begin again anytime.

Mount Rainer is the highest peak in the Cascade Range at 14,410 feet (view from Tacoma, below). The mountain was much taller until a major eruption 5,600 years ago opened a large crater on the northeast side, similar to the open crater that formed at Mount St Helens in 1980. Subsequent eruptions rebuilt the summit and filled the collapse crater. Some of these eruptions melted huge quantities of snow and ice and created the lahars that reached as far as the Puget Sound lowlands, some 30 miles distant. The last major eruptions from Mount Rainier were of lava flows around 2,200 years ago and pyroclastic flows about 1,100 years ago. In the 19th century early settlers reported steam explosions from the summit, but no geologic evidence of this activity has been found, so this possible activity is considered tenuous.

Mount Hood, Oregon’s tallest peak, has erupted repeatly during the past 500,000 years. The broad flanks of the mountain are formed by numerous sequences of lava flows. The growth and subsequent collapse of lava domes, and many fast-moving pyroclastic flows and lahars, are the dominant features of the recent history of this volcano. This volcano had a significant eruptive period about 1,500 years and then another late in the 18th century. In 1859 and 1865 early settlers in the area referred to ash, flying rocks and voluminous steam that likely marked modest explosive eruptions.

Three Sisters are prominent volcanoes surrounded by a cluster of volcanoes in central Oregon. This cluster is unusual, as typically there is a 50 mile or more spacing between volcanoes in the Cascades. Each of the Three Sisters formed at different times and from different magma sources. The North Sister and Middle Sister have not erupted within the past 14,000 years, but South Sister last erupted about 2,000 years ago. Satellite imagery showed that the ground near South Sister was beginning to buldge upwards in 1997, signaling the rise of a pool of magma that was moving towards the surface. Hundreds of small earthquakes were also recorded in the area of uplift in 2004, but eventually the activity subsided.

These four volcanoes, as well as other Cascade volcanoes, are very episodic in their eruptive behavior. They can exhibit frequent eruptions over periods of decades to centuries, but then can be dormant for thousands of years. Monitoring of the volcanoes is essential to provide alerts and take precautions against the hazards. When a large eruption occurs there could be a very high death toll, billions of dollars in property damage, major disruptions of transportation corridors, and the lives of tens of thousands of residents in the Pacific Northwest and surrounding areas could be disrupted for many years. Preparation will be key.

SOURCES AND MORE INFORMATION

Volcano assessments: https://volcanoes.usgs.gov/vhp/assess.html

Ewert, J.W., Diefenbach, A.K., and Ramsey, D.W., 2018, 2018 update to the U.S. Geological Survey national volcanic threat assessment: U.S. Geological Survey Scientific Investigations Report 2018–5140, 40 p., https://doi.org/10.3133/ sir20185140. https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/sir20185140

Strader, S.M., Ashley, W. and Walker, J., 2015. Changes in volcanic hazard exposure in the Northwest USA from 1940 to 2100. Natural Hazards, 77(2), pp.1365-1392.

PHOTOS

Mount St Helens eruption — https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:MSH80_eruption_mount_st_helens_05-18-80-dramatic-edit.jpg

Map of Cascadia Volcanic Arc — By NASA/Black Tusk – NASA World Wind, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5007971

Chart showing eruption frequency — By Black Tusk – Own work, CC BY-SA 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=5109264

Mount Rainier from Tacoma – photo by Lyn Topinka (USGS), 1984 –https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mount_Rainier#/media/File:Mount_Rainier_over_Tacoma.jpg

If you like my posts, please scroll down to the bottom of this page and leave your email address on my website. You’ll receive messages only when I publish a new post (about once a week) and my occasional newsletter. Join now to stay up-to-date about culture, geography, and history.

Leave A Comment