Earthquakes have destroyed settlements and wreaked havoc on societies throughout human history, either by severe shaking or by triggering avalanches, landslides, and tsunamis. Shaking intensity relates to the underlying rock units and distance to the fault rupture. In my soon-to-be published book, The Monumental Andes, I speculate that a major earthquake, perhaps combined with disastrous effects from El Nino weather patterns, could have contributed to the downfall of the Chavín culture that once flourished in the Cordillera Blanca region of modern northern Peru. I briefly describe this idea and information about earthquakes in the area below in this post.

First, a photo of the prominent trace of the active Cordillera Blanca fault that ruptured the ground surface in the Chavín region around 2,000 years ago. The linear scarp is part of a series that tracks across the landscape for tens of miles. I took this photo during a visit to the Cordillera Blanca region as part of my book research. My geologist friends and I expected to see the fault trace in this area, but when it came into view, the prominence of the feature impressed us.

Scarp on the Cordillera Blanca fault east of Huaraz, probably formed in an earthquake that occurred about 2,000 years ago

A Society That Thrived for Hundreds of Years

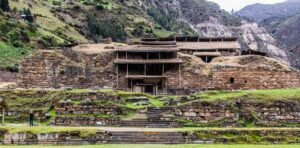

Chavín de Huántar, an ancient sprawling temple complex in a narrow valley high in the Andes Mountains, was once the center of a powerful cult and an important pilgrimage site. When I visited this site, the monumental structures, the setting with two rivers flowing nearby, and the exposures of bedrock in the area fascinated me. In my research, I found that archaeologists and a talented geologist had uncovered some mysteries about the site, which I describe in The Monumental Andes. In a few previous blog posts, I’ve included some of this information (here are the links: Water and Power at Chavín de Huántar, Fangs and Claws of Gold – Supernatural Creatures in Ancient Chavín Art, and Tales of Transformation at Chavín de Huántar).

The Chavín culture flourished for centuries, and their religious traditions influenced many distinctive societies in coastal and highland areas throughout a large geographic region. Beginning as early as 1,400 BCE, the builders of Chavín de Huántar began landscape modifications to level the future building sites of their temples. Detailed detective work by archaeologists has led to the identification of five major construction stages, with at least fifteen separate phases of work. The most massive and intensive construction took place from roughly 1000 to 800 BCE.

Chavín de Huántar, built around 3,000 years ago (Wikipedia)

Many pilgrims traveled to the temples from throughout a wide region, carrying distinctive pottery and other gifts. One room in the temple contains an exotic 15-foot-high (4.5 m) granite sculpture of a deity with a mixture of human and animal features, including claws for fingers and toes and hair formed by writhing snakes. Above the sculpture is a single large floor stone that someone could remove, allowing a person to speak unseen for the sculptured figure below. This unique feature has led archaeologists to interpret the sculpture as an oracle who would have communicated with privileged supplicants.

And then, in the one hundred years after about 500 BCE, following a period of extensive renovations of the temple complex, social instability ensued at Chavín, and the culture collapsed.

Intriguingly, around the same time as the fall of Chavín de Huántar, there was a similar decline in other Andean coastal and highland centers. Specifically, these were settlements along the Pacific coast and in the mountains directly above. These sites happen to coincide with the region that is most subject to disruption from the heavy rains and flooding of the El Niño weather pattern, which began increasing in frequency and intensity around 3,000 years ago. To the ancient Andeans, the dark clouds that could bring heavy rain and flooding seemed to originate in the highlands. They didn’t understand that the warmer ocean waters of El Niño, and the disruptions to the environment, developed in the far western Pacific Ocean.

The combination of an intensification of devastating El Niño events, combined with a major earthquake, or landslides that followed an earthquake, would have resulted in chaos. And these events could have turned the local populations against those who claimed the ability to intercede with supernatural forces.

The historical record holds tantalizing hints. An earthquake on the Cordillera Blanca fault, located close to Chavín de Huántar on the west, would have caused major damage and many fatalities. Geologic investigations suggest that roughly 1500 to 2000 years have elapsed since the last major earthquake on this fault zone (described below). There can be large uncertainties in accurate timing of medium to large earthquakes. It is possible that sometime around 500 BCE, a major earthquake on the Cordillera Blanca fault zone shook the region severely.

There are even indications of probable earthquake damage in a section of temple where builders had recently completed construction; shortly afterwards, people abandoned this ceremonial center. In both local and more regional disasters, if an oracle who was an important part of the religious establishment at Chavín de Huántar did not predict major flooding or a large earthquake, and didn’t warn of the deaths and destruction that followed, then perhaps people turned away from Chavín leaders?

Finding Faults in the Andes

The dramatic exposures of the active Cordillera Blanca fault are visible along the road between the city of Huaraz and the archaeological site of Chavín de Huántar. West-facing fault scarps, or low cliffs, mark the fault trace and form a distinctive line as they march across the landscape for about 75 miles (120 km). On one side of the fault zone are young granitic rocks (Miocene and Pliocene); on the other side are much older sedimentary shales composed of silts and clays deposited onto an ocean floor from a slow rain of sediment (Mesozoic). The fault displaces glacial moraines, the large piles of gravel that were left behind when ice retreated at the end of the Pleistocene Ice Age. These moraines range in age from 11,000 to 14,000 years old.

Detailed geologic studies of the Cordillera Blanca fault near Huaraz reveal evidence of at least five and possibly seven surface-faulting earthquakes. Each of these earthquakes displaced the glacial moraines, so we can confidently assume they occurred within the past 14,000 years. Geologic data suggest that roughly 1,500 to 2,000 years have elapsed since the last major earthquake. The ground surface appears to have moved vertically by about 6 to 9 feet (1.8 to 2.7 m) in each earthquake. These are large breaks in the Earth’s crust, showing that each event was powerful and likely had a magnitude of 7 to 7.5.

Surely these earthquakes would have affected the ancient Andeans, and they probably wondered why their earthquake deity was angry. Sometimes, earthquakes can trigger the collapse of a society. Maybe this happened at Chavín de Huántar? We will probably never know for certain the events that brought this sophisticated culture to an end, but natural disasters are high on the list of potential causes.

If you liked this post, please share it and/or leave a comment or question below and I will reply – thanks! And if you’d like to receive a message when I publish a new post, scroll down to the bottom of this page, and leave your email address on my website. Join now to learn more about geology, geography, culture, and history.

Fascinating. The photos of the scarps are very cool!

Thanks, John!

Excellent citation of the JGR paper by my friend David Schwartz. Yes, judging from the spectacular fault scarps, these paleo-earthquakes were likely Magnitudes 6, 7, or perhaps 8

Thanks for the comment — definitely impressive scarps and an investigation that indicates large magnitude earthquakes!

A more precise chronology for the human occupation of Chavín de Huántar is provided by Richard Burger: “The chronometric estimates for the Chavín de Huántar ceramic chronology are as follows: Urabarriu Phase (950–800 cal BC), Chakinani Phase (800–700 cal BC), and Janabarriu Phase (700–400 cal BC). The new measurements confirm the sequence of the ceramic phases and indicate that the site was established around 950 cal BC and was abandoned by 400 cal BC.” (Richard Burger, “Understanding the Socioeconomic Trajectory of Chavín de Huántar: A New

Radiocarbon Sequence and Its Wider Implications”, Latin American Antiquity, Vol. 30, No. 2 (June 2019), pp. 373-392).

Thank you for this comment. I am aware of Richard Burger’s chronology. I also rely on some of the dates that John Rick and colleagues developed. I understand there is some controversy about the human occupation chronology, but there is also significant uncertainty in exact dates of earthquake occurrence.