Ancient people collected, transported, and shaped enormous rocks—known as monoliths—for thousands of years. They dealt with impressive sizes and weights when they carved gigantic statues and shaped stone blocks for pyramids, temples, and other monumental structures. The availability of different rocks, and where people quarried the chosen types, fascinates me. (Most geologists are fond of rocks….) Note: a monolith is an ancient sculpture, obelisk, or column formed from a single large block of stone (mono as in “one”); a megalith involves one or several stone slabs of great size (mega as in “huge”.)

Many ancient societies carved monoliths. Perhaps the oldest known in the world are the massive stone pillars found at the Neolithic archaeological site of Göbekli Tepe in Turkey. This mysterious hilltop settlement, constructed between about 9500 to 8000 BCE, contains at least 200 T-shaped limestone pillars. Most pillars range in height from 10 to 18 feet (3 to 5.5 meters), and the ancient people installed these in large circular structures. They quarried the pillars from dense limestone bedrock in pits next to the buildings.

Göbekli Tepe with circular structures containing enormous T-shaped stone pillars, built and occupied circa 9,600 to 8,000 BCE. (Wikipedia)

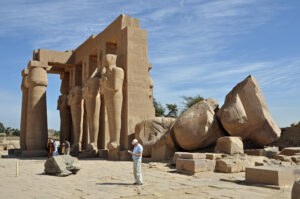

Among the largest ancient monoliths are the Colossi of Memnon, two Egyptian statues that each weighed about 700 tons. (One ton—specifically a short ton in the United States—is 2,000 lbs, or about 907 kg; this is the approximate weight of a small electric car, or a cow or walrus.) Around the world, laborers quarried many monoliths from rocks found within a short distance. But if a special type of stone was the preferred material, then the ancient laborers would move gigantic stones for tens and even hundreds of miles. Archaeologists have debated the source of the stone for the Colossi, with one possible source a quarry near Aswan in southern Egypt and another quarry near modern Cairo (Gebel Ahmar; this likely would have required transport of the monoliths for 420 miles/675 km overland).

The Colossi of Memnon, shaped from single blocks of silicified Nubian Sandstone (quartzite), are statues of the Pharaoh Amenhotep III that originally stood guard at the entrance to the pharaoh’s memorial temple. They have stood in Luxor (formerly Thebes), Egypt, since 1350 BCE. Over the millennia, different types of sandstone blocks have been added in reconstruction attempts. (Wikipedia)

I learned about many of the quarries used by the ancient Andeans as part of the research for my soon-to-be-published book (working title: The Monumental Andes: Geology, Geography, and Ancient Cultures in the Peruvian Andes.) and I’ve shared some of this information in previous blog posts. The ancient Egyptians are particularly renown for working with enormous rocks, so I describe aspects of that topic in this post.

An Abundance of Rock in Ancient Egypt

Rocks played a major role in the religious practices of ancient Egypt. For almost 3,000 years, various dynasties directed the use of monolithic blocks in temples, pyramids, tombs, and enormous statues. The vast available quantities of sandstone, limestone, and igneous granitic and volcanic rocks made this possible. Archaeologists recognize approximately 200 quarry sites in Egypt, with the majority next to the north-south Nile River that provides a lifeline for this desert region. Intensive quarrying required significant logistical organization, and so it took place only during periods of strong royal power. During different historical periods, various quarries were worked depending on the rock preferences of the time.

Black granite sarcophagus, circa 1350 BCE, originally from Thebes and now in the British Museum (Wikimedia)

My interest in the ancient Egyptians and their quarries began in the mid-1980s while I was employed in southern Egypt for several months as part of a group studying earthquakes near the Aswan Dam (described in my post: Earthquakes, Copper, and Helicopters.) Living and working in the town of Aswan, we could visit impressive archaeological sites during our occasional free days. The Aswan area contains many quarries used for the magnificent Egyptian stonework. On one excursion, we were fortunate to see the “Unfinished Obelisk”—an enormous piece of granitic rock that Queen Hatshepsut (1508-1458 BCE) reportedly commissioned, but which was abandoned after cracks appeared in the rock. If workers had finished this obelisk, it would have measured around 137 ft (42 m) tall and weighed nearly 1,200 tons—far larger than any ancient Egyptian obelisk ever erected.

The “Unfinished Obelisk” at a quarry near Aswan, circa 1500 BCE (Wikimedia)

The Aswan quarries contain a highly recognizable and notable granitic rock that is pink to reddish-pink, coarse-grained, and known as “rose-granite”. The ancient Egyptians used this distinctive rock in many monolithic carvings, including the massive unfinished obelisk.

The pink “rose granite” from quarries near Aswan, used for many obelisks (Wikipedia)

Other rocks that were quarried in the Aswan area and used widely throughout ancient Egypt are gray to black granitic rocks (granodiorites and tonalites). With granitic rocks, workers typically shaped colossal statues and obelisks directly from outcrops of rock, although sometimes large boulders were the starting point for carvings.

The geologic history of Egypt includes millions of years when shallow seas covered the region, and extensive areas of limestone (mostly Eocene age) occur on both sides of the Nile River. The limestone characteristics vary, and quarry workers concentrated on dense, hard types that lacked fossils. Most of these are in the northern half of Egypt, with the best quality limestone near the Great Pyramids. For the pyramids, laborers moved enormous amounts of limestone blocks from quarries along the eastern edge of the Nile, especially from areas about 100 miles (30 km) distant from the pyramids. They used the best quality limestone for casing material on the pyramids, with the less resistant and lower quality rock used for the tremendous volumes of core material in dozens of pyramids. Ancient workers excavated many of the limestone quarries deep into the Nile cliffs, where they could then load the blocks onto boats and transport them on the river. Today, the Egyptian government uses most of these ancient quarries as military ordinance depots, so they are not available for archaeological investigations.

The Giza Pyramids near Cairo (Wikipedia)

In parts of the Eastern Desert of southern Egypt, between the Nile River and the Red Sea, are extensive outcrops of volcanic basalts, metamorphic schists, and green siltstones and sandstones, that have been partially metamorphosed, making them denser. In one area that was extensively quarried, the outcrops have a favorable parallel joint (fracture) pattern that provided the quarry workers with conveniently sized large blocks of suitable construction stone. (The area is Wadi Hammamat, now a dry riverbed, that provided a major trade route to the Red Sea and then along the Silk Road to Asia). The importance of these quarries is indicated by hundreds of rock inscriptions, including drawings documented to as early as about 4000 BCE. (Other ancient societies also made good use of “natural quarries” that are a result of tectonic folding and faulting; these include the natural outcrops of granitic rocks that Inca builders used to build Machu Picchu [see Monuments, Megaliths, and Inca Builders ].)

In southernmost Egypt, the ancient people used outcrops of Nubian Sandstone (Cambrian to Cretaceous age) extensively for sacred Egyptian monuments and statues. Similar to the limestone quarries, tall escarpments eroded into the outcrops by the waters of the Nile River provided ideal quarry sites for the ancient people. Archaeologists have used well-preserved rock inscriptions and even different chisel marks on quarry walls to define specific historical epochs when the ancient quarries were worked. The massive statues of Abu Simbel, the monument that was relocated from the rising waters of the Aswan Dam in the 1960s, were cut into Nubian Sandstone (a short description and good photo of the reconstruction are in my post Protecting Significant Sites in Egypt, Peru and Beyond.)

Some outcrops of Nubian Sandstone are hard and resistant, with strong silica cement, but most is only moderately to poorly cemented and crumbly. Due to the arid climate of Egypt, even the less resistant sandstones have survived in structures and carvings for millennia. In recent decades, however, irrigation practices that increase the salt content of the soil are causing the rapid deterioration of the basal parts of many ancient sandstone monuments. (Nubian Sandstone covers a large area of northeast Africa and the Arabian Peninsula; the ancient temples and tombs at Petra in Jordan are carved into this rock and also threatened by weathering from salt upwelling.)

Mortuary temple of Pharaoh Ramesses II (Ramesseum) in Luxor, constructed of Nubian Sandstone, circa 1400 BCE (Wikimedia)

Moving monolithic blocks from quarries to construction sites was undoubtedly a major challenge for the ancient people. Many enormous stone blocks from quarries along the Nile River were transported by boat on the river and then in channels excavated by the ancient workers—I’ve written about this in a blog post (see Ancient Boats and Enormous Blocks). Archaeologists at the unfinished obelisk site have identified traces of a trench at least 8 ft (2.4 m) deep that extended toward the Nile River, possibly deepening as it neared the river, and this channel was likely planned for floating the massive obelisk downstream to its planned location. Other blocks came across desert tracks for perhaps as far as hundreds of miles. Human muscles were used to drag these using rope harnesses, possibly on sleds along prepared roads or tracks. We have lost many details in the dust of history.

***********************

Around the same time the Egyptians were shaping monolithic blocks, Neolithic people were arranging enormous stones in a circular pattern at Stonehenge, constructed from about 5000 to 4000 years ago. I’m especially intrigued by Stonehenge, as well as by the giant human-like sculptures at Easter Island, and in Part 2 and Part 3 blog posts I’ll share what I’ve learned about the rocks at these archaeological sites.

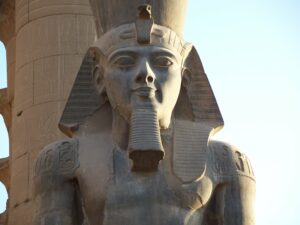

Ramesses II Colossus in Luxor Temple (Wikimedia)

If you liked this post, please share it and/or leave a comment or question below and I will reply – thanks! And if you’d like to receive a message when I publish a new post, scroll down to the bottom of this page, and leave your email address on my website. Join now to learn more about geology, geography, culture, and history.

That’s a lot of heavy lifting

Definitely — thanks!

Another fantastic article! Thank you for sharing the knowledge and insight you gain on your travels.

Thanks, Larry! I really appreciate your comment!