From maize-based chicha, or corn beer, in the Andes Mountains, to mead from honey in ancient Greece, and wine from grapes in Predynastic Egypt, fermented beverages have been a part of cultural rituals for many thousands of years. Celebrations that include copious amounts of alcoholic drinks and specially prepared foods have been widely practiced in numerous cultures over time. In ancient societies, feasting played a prominent role in the emergence of social hierarchies and was important in shows of power.

Alcoholic beverages have been used to control empires, establish trade relationships, and manipulate the world economy. Fermentation to produce alcohol is a process that humans have sought to manipulate for at least ten thousand years, and possibly much longer. As the most widely used psychoactive agent on Earth, it has important roles in religious, social economic and political realms. Ethanol is responsible for the psychotropic properties of alcohol, but beyond the common presence of this chemical in alcoholic beverages, the ingredients used, preparation techniques, consumption methods, moral evaluations, and many other characteristics are highly symbolic and culturally specific.

Discovering Fermentation

The characteristics of fermentation were probably recognized initially when biting into a piece of fruit or sipping a liquid from fermented plant material. A discovery dated to around 40,000 years ago in a cave in South Africa suggests that hunter-gatherers were making a type of honey-based alcohol that is a possible progenitor of a type of mead made today by the nomadic San peoples in that region.

As early as 9,000 years ago, and possibly much earlier, rice, honey and fruit were used in China to produce wine. Within a few thousand years, wine-making was also well established in Persia (Iran), the Southern Caucasus of Eurasia (modern Armenia, Georgia, and Azerbaijan), and modern Turkey and Sicily.

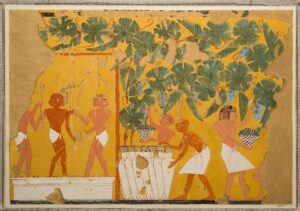

Mural from tomb of Ipuy, New Kingdom, Egypt, circa 1279-1213 BCE

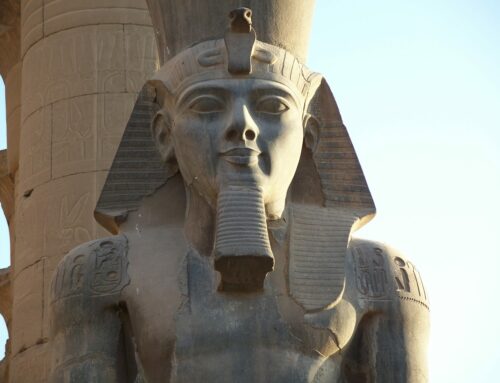

Around 6,500 years ago, Egyptians from the Predynastic period were placing jugs of wine in tombs. Fast forward to about 4,500 years ago, and they were illustrating grape production and winemaking processes on tomb walls. For the next 2,000 years of Egyptian history, ancient images show a process for winemaking that is similar to that used by winemakers in the Mediterranean regions today. By the time of European colonial expansion in the 15th century, only some parts of the Pacific Islands and North America were without indigenous versions of alcoholic drinks. The locals quickly adopted the new introduced beverages (of course, sometimes to the detriment of at least some of the population).

In the Andes, alcoholic beverages were particularly valued in ritual contexts for thousands of years. Sharing food and drink, as gestures of hospitality and in reciprocity to return favors received of labor or goods, are a cornerstone of ancient Andean cultures. Maize, the key ingredient preferred by many to make the chicha, was probably used for the fermented beverage long before it became an important food item. In a recent post about maize, I’ve also written about chicha – you can check it out here: https://roseannechambers.com/marvelous-maize/.

Obligatory Inebriation

In many ancient Andean societies, relationships with ancestors, both in a direct lineage and those mythical founders who emerged from underground or from the sky, were fundamentally important. Feeding the ancestors was an essential part of rituals. One way to honor them was to pour special liquids into the ground, so chicha for this purpose became a part of many ceremonies. Fermented beverages transformed participants, so it was also believed that the ancestors could be fed through an individual’s consumption; by filling up with drink, the extra could then be transferred to the ancestors. Excessive drinking at feasting events was encouraged, even obligatory, and since these events could go on for many days, participants would be strongly affected. (Needless to say, following the arrival of the Spanish in Inca lands, the Catholic Church was opposed to these practices.)

During the Inca Empire, the appreciation of chicha reached a pinnacle tied in part to the recognition of maize as a food of the gods. Special imperial ceramic vessels were used to make and serve this beverage for the frequent state sponsored feasts, and the broken bits of these richly decorated containers are found throughout the thousands of miles of the empire. Vessels known as aríbalos were filled with chicha, and imperial versions were remarkably standardized in shape and proportions. These were produced in sizes ranging from miniature, filled with chicha and left as offerings in the tombs of elites, to ones so large they were difficult to move.

Aríbalo for chicha, Inca Empire, circa 1430-1532

The preparation of chicha was a major culinary task for women. Since chicha can take several weeks to make, and then spoils fairly quickly, producing the enormous volumes needed for the large public gatherings became a daunting task. The Incas solved this by establishing a tradition of “chosen women” who lived together in special quarters and whose major task was to make chicha for the state. Conveniently for the emperor, the young women also provided a “pool” for when a human sacrifice was needed, or else they could be selected to be wives for important men in the empire. (I’m grateful I wasn’t born in that era!)

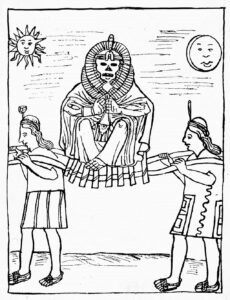

Feasting with Mummies

In the Inca world, the mummies of the dead rulers played an active role in the lives of the living. After the deaths of emperors, their mummies would continue to be housed in the original palaces in Inca Cuzco and they would be displayed to the public during special ceremonies. Sharing food was a fundamental expression of kinship in the Andes, so during feasts, the best food and drink were shared with the mummies. The actual items were conveniently consumed by retainer-priests, who acted as conduits to the mummies (a tough job – but someone had to do it). In this way, the living and dead were thought to be celebrating together in a harmonious community!

Incan mummy, illustration by Huaman Poma de Ayala, 1551-1615

Foods that were served at Inca feasts included potatoes and other tubers (including the exotic ulluco, mashua, maca and oca), quinoa (a seed in the amaranth family), plus vegetables of many types including greens, with seasonings of red chili peppers and salt. Commoners typically ate much less meat than the elites, so special occasion feast foods were dried or freshly roasted meats that could include fish, duck, llama, and guinea pig. And of course, copious amounts of chicha were always provided.

A holiday toast to you, dear reader! And – I’m signing out for the last couple of weeks of December – back online early in 2021. Wishing you and yours warm and enjoyable (if very small and quiet) holiday celebrations – and best wishes for a happy, healthy, and adventurous New Year!

SOURCES

Dietler, M., 2006. Alcohol: anthropological/archaeological perspectives. Annual Review of Anthropology, 35, May, pp.229-249.

Editors of Archaeology, 2020, Alcohol Through the Ages: Archaeology, Vol. 73, No 6, November/December, p. 26-33

Hastorf, C.A., 2003. Andean luxury foods: special food for the ancestors, deities and the élite. Antiquity, 77(297), pp.545-554.

Photo of urn in featured image; https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Inca_Urn_LACMA_M.71.73.238.jpg

Photo of mural showing winemaking from the Tomb of Ipuy Metropolitan Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Winemaking,_Tomb_of_Ipuy_MET_30.4.118_EGDP022609.jpg

Photo of urn: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Civiliza%C3%A7%C3%A3o_Inca_-_Ar%C3%ADbalo_MN_03.jpg

Illustration of Incan mummy by Felipe Huaman Poma de Ayala, circa 1615, Illustration from the book El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Momia_Inca_-_Guaman_Poma_de_Ayala.jpg

If you like my posts, please scroll down to the bottom of this page and leave your email address on my website. You’ll receive messages only when I publish a new post (about once a week) and my occasional newsletter. Join now to learn more about geology, geography, culture, and history.

Thank you, Roseanne, for all your posts this year. I have really learned a lot in various fields.

So now let me raise my glass with some fermented Hungarian beverage in it (called szilva pálinka, i.e. plum brandy) and I wish you and your family a merry Christmas and a Happy New Year that will surely bring new interesting posts from you. Cheers, István

Thank you István! I’m so glad that you like my posts — and I’m happy that we are in contact again after several decades! A toast with szilva pálinka sounds delicious — and I will return the toast to you and yours with a hearty red California wine! Enjoy the holidays — and thank you for the note!

Great work with this blog, Roseanne. I’m new to it and am loving it. Can’t wait to read more!

Happy holidays.

Thank you! I really appreciate hearing from you! All the best for the holidays and beyond!

A colleague from Ghana would always poor his first sip of any alcoholic beverage on the ground as libation for his ancestors. I assumed it was a tribal custom, but it sounds like libation is widespread. Fascinating. Merry Christmas to you and Bob, Roseanne!

Cheers!

Interesting to hear this — thanks Steve. And thanks for the good wishes! My best to you and Carolyn!